For Successful Engagement with UX Professionals),” helping provide additional insights about UX professional personas and critical information that optimizes interpersonal relationships between UXers and stakeholders.

Have you ever been in a meeting where someone who (truthfully) lacked viable design expertise presented an idea and desired that it be accepted — without any real proof or any sound reasoning? Of course you have. You may have been the guilty party. Not to worry, though. We’re here to learn right? In this segment of the “UX Relational Factoids” posts, I felt it would be beneficial to address an aspect of UX that usually goes undetected and unconsidered — the factor of evidence and how said evidence should help people to embrace input from UX professionals.

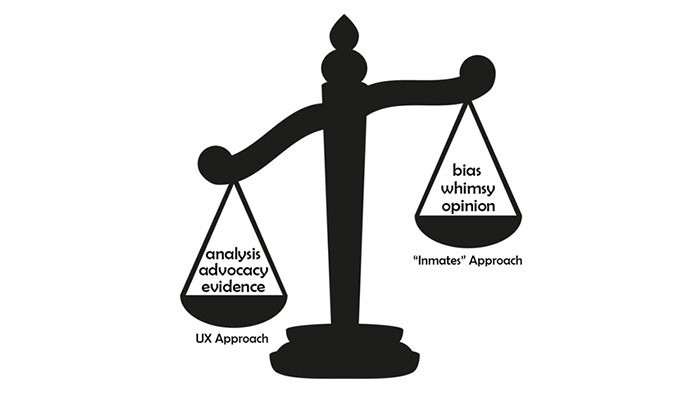

In the project world, input from UX professionals (which consists of and results from analysis, user advocacy, and evidence) is treated (on average) as general opinion and viewed as something that one can take or leave, especially when it contradicts biases, politics, and other acts of whimsy. Truth is, practically any input from a UXer should, at the least, garner some level of investigation before reaching a conclusion.

The dynamics associated with this issue are critical for such an environment as ours. Therefore, let’s take a look at the myth that says “UXers are opinionated” more closely.

Consider the aforementioned scenario, where you’re working on a project that includes an interface. Someone recognizes the challenge presented to the them where an interface will either need to be created or redesigned and offers a solution by suggesting the team follow the example presented by one or two other applications/products. If the team is unaware of design principles, considering the popularity and/or success of the product/app that was suggested, the suggestion will be embraced and the team heads in that direction without any examination, without any critical thinking, without any validation of user’s needs or goals, without any user testing…. you get the picture.

Consider the following:

- If you blindly mimic the architecture and behavior of another application or product, you automatically inherit their failures and problems as well as their successes.

- If context of use is ignored or a poor attempt to understanding it is exemplified, users’ wants and needs are an afterthought, resulting in your project easily becoming an exercise in futility.

- If you don’t engage in user testing, you won’t be able to identify and confirm potential successes and failures.

- There is no user advocacy; hence, the design doesn’t qualify as being user-centered.

Everyone focuses on the goal of finality (i.e., trying to complete the project by a specified due date, no matter the readiness of the product) instead of pursuing sound business goals and applying proven methodologies in their approach.

This “inmates” oriented approach (I’ll explain that in more detail at the end of the post), which (frankly) is error prone, counterproductive, and presumptuous, isn’t a wise way to proceed. Now, enter application of the “UX approach.” Consider the following small sample size of examples:

- When a specific app/product is suggested as a model, the UX professional (or someone with a UX mindset) will investigate said app/product and identify its strengths and weaknesses, helping provide direction that distances the team’s efforts away from any faults of the previously suggested app/product.

- Knowing that using one example is grossly taboo and that common conventions aren’t necessarily equivalent with correctness, in addition to examining the aforementioned app/product, an additional wealth of apps/products (anywhere from 50-500) will also be analyzed in an effort to help confirm the validity of the team’s direction.

- Each one of the apps/products analyzed will be examined using proven sets of heuristics.

- Based on the findings, recommendations for how to proceed will be provided (zero whimsy, zero bias, zero personal opinion) — with all recommendations based on evidence.

Of course, the process is more in-depth than what’s listed here, but there’s enough information to illustrate the purpose of the post. A proper UX mindset is void of bias, whimsy, and personal opinions. A proper UX mindset is based on analysis, user advocacy, and evidence that comes from heuristics and/or findings from user testing. This approach far outweighs ANYTHING that can or will be provided via the “inmates” side of the spectrum.

I did promise to explain what’s meant by “inmates,” correct? Noted user-centered design expert, Alan Cooper, wrote a book called ‘The Inmates Are Running The Asylum.” This book focuses on how design efforts are (basically) hijacked by people (“inmates”) driven by such things as bias, whimsy, opinion, politics, profits, etc. and the gross consequences associated with such approaches and factors. In our efforts to become a more design-led company, in addition to achieving, embracing, and applying a sound UX mindset, everyone will also need to understand that successful design absolutely CANNOT be driven by “inmates.” In addition, its critical to understand the persona traits and codes of ethics of the UX professional (why we do the things we do and say the things we say). Otherwise, there will never be a sense of appreciation for what we bring to the table and our contributions and leadership will be discarded and ignored. This is also covered in Cooper’s book, where he cites how programmers have a history of hearing so many suggestions about design direction that don’t pan out that, eventually, all such statements are considered as nothing more than “advice” which they can take or leave. While this might be safe in some cases, the persona of the UX professional, being an expert opinion (as opposed to a general opinion) should be immune from such treatment, but that’s not the case. Design failure will result from such a dysfunctional interaction. The inmates’ mindset must be overcome, but the inmates must be willing to opt in or we’re all in for some painful times and the UX professionals must be patient while the inmates make their transition.

The inmates are skilled (at their specialties). They’re great at what they do. From a design perspective, the problems arise when (as Cooper states and implies) “dogs attempt to be cats” and “foxes are consulted about henhouse security.” These are tough truths to swallow, but extremely beneficial.

This post is extremely condensed and I’m sure that many discussions can and will result. Most, if not all discussions are, however, good and worth having. And the more we engage, the more mutual professional respect will be fostered and the more benefits will abound. The quicker said persona traits are understood, the quicker we’ll achieve desired UX maturity states and the more compliant we’ll be to optimal UX cultural structures.